This fall, I had a piece come out in Feminist Anthropology. “Recomposing Kinship” is my attempt to get anthropologists (and others) to take technology more seriously as a social actor–or at least as something more than an object of fetishism. It’s something like my 20th article, and over the last 15 years of publishing, I’ve found that how I approach revisions on articles has developed into a system. This article, by way of example, first received a revise & resubmit, and then was accepted for publication after a second set of reviews were returned based on the revision. Parts of it had be presented at conferences or in workshops, but it had never all been put together before, so sending it out for peer review was a bit of a fishing attempt–I was really curious to see how people responded to an argument that put together Facilitated Communication, sleep apnea, genetic testing, and fecal microbial transplants.

I’ll chalk the speed with which I was able to turn things around and address reviewers’ concerns to 15 years of academic publishing–and that the piece grew out of a couple of projects that have had pretty long gestation periods. It was also really helpful that the reviewers were on board with the conceptual project (even if they didn’t necessarily agree) and that the editors were supportive of a revision. Since the process of revision has become largely the same for me, it seemed like a good opportunity to write about the process in case it helps other people approach their own revisions.

Whenever I get emails from editors about articles under review, I really try not to open the email immediately. I find that whatever the email’s contents, it’s likely to derail me for the rest of the day, usually due to a desire to get back to work on the article. I try, whenever I can, to save it until the end of the work day. That way, after I read it, I can mull over the contents while I cook dinner, take care of the kids, feed the dog, chat with my partner, etc. This helps to stop me from wanting to address the editorial and peer review comments right away and lets them simmer as I do some ambient processing. Generally, other work gets in the way of immediately getting back to the manuscript and so I try and take a week off of working on it.

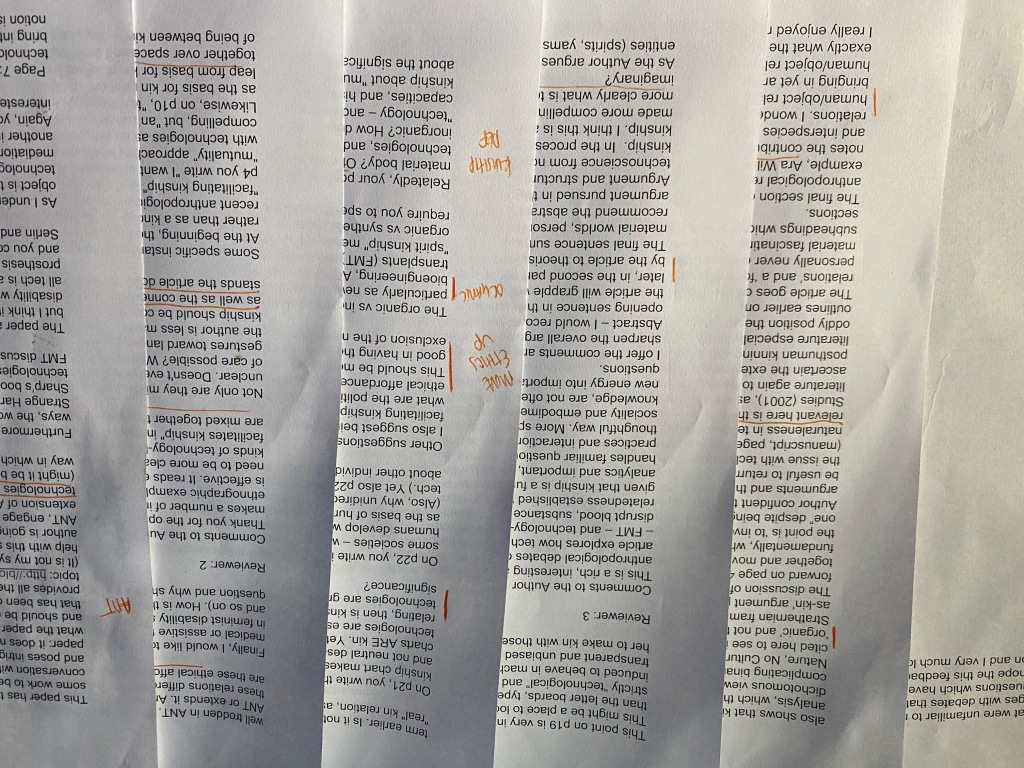

When I get back to working on revisions, I start by rereading the cover letter from the editor and reading through the peer reviews. I read them in their entirety and then read them again. On the second pass, I try and come up with a list of the necessary and optional revisions. A lot of peer review is relatively phatic language which can sometimes distract from what the peer reviewers are actually asking for; I tend to underline the relevant parts of the peer reviews and make marginalia to help me extract the incisive parts of the peer reviews. I then write them up and group them–if reviewers are asking for the same kind of thing (or contradictory things) this helps me develop a sense of what kinds of overlaps there are in the reviews. (You can see examples of my underlining and marginalia above.)

With that list of optional and necessary revisions developed, I set about grouping them. The first pass at grouping puts similar kinds of suggestions together, and the second grouping pass orders the suggestions in terms of where they should appear in the body of the revised manuscript. This usually involves sorting suggestions into multiple parts of the introduction (opening, literature review, map of the article, thesis & argumentation), each of the substantive sections, the conclusion, and citations and endnotes. I find that the heaviest lift is the suggestions for the introduction, followed by the conclusion, and then the substantive sections of the paper, which usually most need clarifying and alignment with the article’s aims once I’m able to clearly state them and articulate their relationship to the evidence at hand.

I then try to address the suggestions in order of difficulty. Overlooked citations come first, with minor syntactic tweaks following, and then it’s on to the big issues.

I’ve found that one of the recurrent experiences I have is overlong introductions. I try and make them short and to the point, but after addressing reviewer suggestions, I find that introductions balloon to be 7-8 pages long, when they should be 4-5 pages. If I can, I move parts of the introduction into the endnotes–especially theoretical positioning that only certain readers care about–but I’ve increasingly begun to break introductions into two parts. The first of these parts is the usual, empirically-driven hook that readers tend to appreciate which helps to set the stakes of the piece. It’s followed by the thesis and a layout of the article’s structure. But then I have a second helping of introduction, which is usually the literature review and theoretical work. If possible, I break these sections apart with headings to make sure that they are clearly flagged for reviewers and readers. I wish I could do this in the initial writing of an article manuscript, but I’ve come to find that it’s really only through revision that I’m able to see where these breakdowns should be–usually as a direct response to peer reviewer suggestions.

Often, working through the revisions means substantially rewriting the conclusion. Conclusions are always hard for me to write, often because, generically, they waffle between recapitulations of what was just written and soaring calls for reimagining disciplines, theoretical frameworks and categories, humanity, and existence. I try and do a little of both in an initial manuscript draft and then rework the conclusion based on reviews.

When I resubmit a revised article, I always make sure to include a very detailed cover letter to guide the editor and peer reviewers through the revisions. It’s usually pretty easy to adapt the list of suggestions for revision into a cover letter. Where possible, I make sure to flag where a suggestion came from–i.e. which peer reviewer or the editor–and detail how it is addressed in the revised manuscript. I also try and include a page number and paragraph to make sure that it’s very obvious. One of the challenges I’ve faced as a reviewer over the years is having the original version of an article in mind as I review a revised manuscript. I imagine other readers have similar issues, and it’s particularly helpful to dispel specific concerns by addressing them in the cover letter in addition to the manuscript.

I recognize that this is all pretty dispassionate in its approach. And it’s true: I’m pretty dispassionate in my writing. Most of what I enjoy about writing is solving puzzles, particularly how to put certain kinds of evidence and argumentation together. Addressing peer reviews is a lot like solving a puzzle to me. Given all of the pieces that reviewers have provided me with, how can I fit them together into a coherent picture that abides by the aims of the original version of the manuscript (or “picture” in this metaphor)? Sometimes it’s harder than other times, and it requires some finesse in smooshing pieces together. Other times it’s really clarifying, and I find these to be the best rewriting opportunities.

How do you rewrite based on peer reviews? Other suggestions for techniques? Tell me about them in the comments.

One thought on “How I Revise Articles for Resubmission”