It might seem a little perverse to wait until the penultimate step to discuss introductions and arguments, but like I mentioned in step 2, it’s often helpful to work through most of the other material in an article manuscript first, so that when you get to the introduction and argument you have a clear sense of what your argument actually is. So, if you’ve worked through steps 1-4, getting down to the brass tacks of your argument should be a lot easier than if you try and start with the argument — which can be daunting and freeze many writers in their tracks…

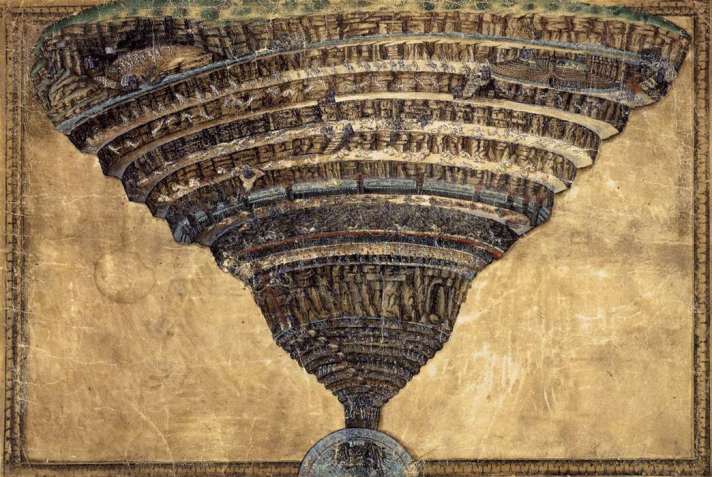

(In case you want to know what my chalkboard writing looks like, here’s the diagram from my alternative spring break.)

(In case you want to know what my chalkboard writing looks like, here’s the diagram from my alternative spring break.)

Often, in cultural anthropology at least, articles begin with a little ethnographic vignette — some kind of hook to get the reader’s interest piqued. As I mentioned in step 4, these vignettes are usually linked to the cases that make up the evidence in the rest of the article, and tend to be about a page or so long.

A successful introduction — ethnographic vignette or not — should give your reader a sense of why she or he should keep reading within a page or two, and a good rationale to keep reading is a question or quandary that’s of broad appeal, but which you can provide the answer for. So, it might be an ethnographic vignette, or some other compelling set of data posed in a way that begs questions rather than provides answers, or it might be a question about the existing scholarly literature, or a case from popular media or current events (although I tend to think that current events don’t stay current for long…). Regardless of what your introduction is comprised of, it needs to be returned to later in the article — and where you return to it should make sense based on what the introduction is (i.e. if it’s an ethnographic vignette, continue the vignette in one of your cases, if it’s a problem in the literature, return to it in the literature review, etc.).

After you have your reader hooked, what will actually keep the reader reading is a well articulated argument. One of the most critical things is to not bury the lead — which is to say, make sure your argument appears by the end of page two of your article manuscript (which means it will be on page one of your published article). If your argument comes too late, you risk losing your reader, or, at the least, having your reader begin to wonder why they’re reading what they’re reading. A good argument, posed early on, will do a lot of work for you and ensure that your reader keeps reading — so don’t get carried away with your introductory hook.

What makes a good argumentative thesis? That’s probably the hardest part of this whole project, and it really takes time and experience to develop a solid thesis that you can substantiate with your evidence. I can’t tell you specifically what will make a good thesis for you, but I can give you a few guidelines, some of which are going to seem like no-brainers:

First, a good thesis is motivated by your evidence. This might sound totally crazy, but one of the biggest mistakes I see in articles I peer review is that the thesis makes evidentiary claims that aren’t supported by the evidential cases in the article. My sense is that this is due to people writing articles linearly, starting with the introduction and thesis and then moving onward, and failing to bring the cases in line with the thesis. But if you tend to your literature review and cases before turning to your thesis, you should have a clear sense of what your contribution to the literature in your field is and how your evidence relates to it. One way you might start here is by writing a sentence like ‘Based on [Case 1] and [Case 2], we see that X is actually X1,’ where X is a particular theoretical concept or assumption about a region and X1 is your claim about the same. Once you have that clunky sentence in place, you can work on revising it into something a little more eloquent…

Secondly, a good thesis poses causality. I’m using ‘causality’ here in the broadest sense of the term, mostly because I need some kind of shorthand for all of the kinds of interpretive work that you might do and need to embed in a thesis. In fact, you might be talking about causality (‘X is now X1, because of Y’), but it might also be a little more subtle than that (‘Attending to Y shows that X is actually X1.). Try a sentence like one of those, where Y is what you’re focusing on in your cases. If your two cases are different from one another, then you probably have two sentences here to explain the nuances that each of the cases adds to your claims.

Third, a good thesis engages with questions in the existing literature. Since you’ll be tackling the literature that’s relevant in your literature review — which is coming up very quickly — you don’t need to get into fine details here, and you can often get away with theoretical shorthand, i.e. you can just use keywords, as long as you return to them in your literature review. The right keywords will often motivate a reader long enough to get them through the introduction — as long as you sincerely engage with them as theoretical concepts and make it apparent to your reader how the terms relate to your argument.

It’s often difficult to capture all of these qualities in one sentence (and unwise). It’s best to break them up into sentences in their own right, or at least to start that way and work towards integration. In the end, you should have a paragraph — and it might be a short one — that brings all of these concerns together and gives your reader a sense of the stakes of what you’re focusing on and a clear sense of why she or he should give you the next 30 minutes of her or his time. The weaker or less articulated the thesis, the less likely your reader is going to stay motivated for the whole article…

After your thesis paragraph, you should take the time to detail your methodology in a paragraph. This paragraph can be difficult to write — mostly because it’s difficult to be excited about it — but once you have a good methods paragraph, you can copy and paste it with minor variations for every article you write thereafter. A good methods paragraph lays out the duration of the research, where the research was conducted and what those contexts were like, and what the sample size was (which, for cultural anthropologists, is the number of people interviewed, events attended, etc. — the stuff that makes up your cases). This paragraph might also legitimate methodological choices in reference to key theoretical-methods literature, particularly if the methods are unconventional or experimental for the audience of the journal.

After your methods paragraph, you should turn to your literature review. By now, you should have a pretty clear sense of why you’re discussing the literature that’s in your literature review, so working through it again to revise it is worth the time. Given your argument, tighten up your literature review, both cutting some literature that’s no longer relevant to your argument, and also making sure that you’re highlighting what you should be about the literature that you’re keeping.

The last paragraph in your introduction should be a transitional paragraph that lays out the content of the article in relation to your thesis. So, often what you’re doing is moving from the fairly broad claims in your literature review to the specific content of your cases and surveying them in a sentence for each case. But this is all preceded by a recapitulation of your thesis in a shortened form. ‘As I will demonstrate in the following, X is due to Y resulting in X1. This can be seen in Case 1, where X is A. Further, in Case 2, X is B.’ That feels a little symbolic-logicky, but hopefully you get the idea. You should also explain what will occur in your conclusion, so there are no surprises, i.e. ‘In the conclusion, I discuss the implications of X as X1 for [subfield or regional interest].’ Basically, you’re once again motivating your reader to carry on reading the article, and also ensuring that there are no substantial surprises — your reader needs to be able to anticipate everything that’s coming up (without all of the nitty gritty details). Anticipation is motivation.

All told, your introduction should be about 5 pages long (maybe up to 7, but rarely any longer than that). Five pages might seem really short, but a good introduction shouldn’t be too long (it’s an introduction, after all) — anything longer than 7 pages is really going to tax your reader, and she or he will be wondering when they get to the good stuff (outside of your opening couple of paragraphs, your introduction isn’t so much ‘good’ stuff as ‘necessary’ stuff). Strive for brevity, knowing that it will help your reader stay motivated. And, when the peer reviews come back, know that you’ll have a little wiggle room in your introduction to address the concerns of your reviews.

Once you have it all weaved together, adding your new introduction to your cases and conclusion, that’s your article manuscript. Easy, right? Now it’s time for some fine tuning…